I recently was able to take a panorama of St Paul’s Cathedral, Dundee. I am releasing an example Hugin PTO file as well as JPG image files to stitch. This example demonstrates a few techniques that may be of benefit to other panographers.

The example files are made available under the Creative Commons licence without guarantee. They are not full size, and the final version on 360Cities has had some post-processing applied so will be slightly different to the version as produced by the example files.

Example files St Paul’s Cathedral, Dundee (ZIP archive)

St Pauls Cathedral, Dundee by Daniel K. L. Oi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Some familiarity with the Hugin program is recommended. The Hugin manual and tutorials can be found at Sourceforge. The examples files included in the ZIP archive include the PTO project files and JPG source images (for reasons of file size) that can be stitched to obtain an exposure fused example panorama.

Shoot Details

The shot patten with a Samyang 12mm/2.8 fisheye lens on the Sony A7m3 is 4 shots taken at 90 deg horizontally, zenith, and nadir. The azimuthal shots were angled slightly down (~10 deg) so to reduce the size of the nadir patch. The tripod legs were also brought in to narrow the stance to help reduce the obstructed area. A nadir adapter on the Nodal Ninja 3 Mk III was used to allow the camera to be positioned directly over the shooting position without the tripod in the way for the nadir shot. An additional shot was also taken from a slightly different position in order to cover the shadow of the tripod and camera.

Note: Usually when taking panoramas, the lens should be rotated around the no-parallax point (NPP) that is located at the lens entrance pupil (EP). The NPP is often erroneously referred to as the “nodal point”. The nodal points of a lens are different to the NPP (see Wikipedia article “Panoramic photographers often incorrectly refer to the entrance pupil as a nodal point, which is a different concept”).

Exposure Bracketing

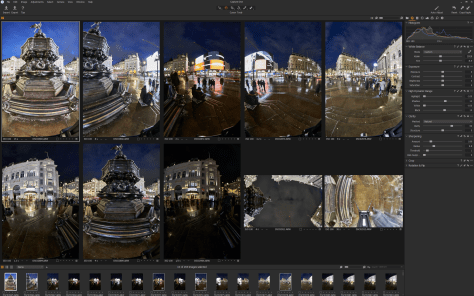

The camera was set to ISO100, image stabilisation off, and a remote shutter release used. Due to the bright stained glass windows, I bracketed exposure -2,0,+2EV. However, I did not need the +2EV shots so only imported the -2EV and 0EV shots. I have placed the shots into stacks. The last 2 shots are the ones to patch the camera and tripod shadow.

Autoexposure and raw processing

Received wisdom is that panoramas have to be taken using fixed manual exposure settings, else the panorama won’t blend properly. This may have been the case 10 years ago but modern software can easily cope with photometric optimisation and compensation of varying exposures throughout a panorama. Exposing each segment of the panosphere optimally will give better image quality overall, in fact. It can save time and effort using autoexposure in cases where the intra-scene contrast is smaller than the inter-scene contrast (in different directions/shots). This can be combined with bracketing if single-shot contrast is excessive.

When processing the raw files, it is recommended that the same white balance be applied to all shots, though there are some circumstances and specialised techniques where different white balances can be used. But normally, the same white balance for all shots will usually result in better blended output.

Shooting raw also has the benefit of extracting the most exposure latitude from each shot. For these shots, I have used the maximum amount of highlight recovery and this has allowed the detail in the windows to be retained in the -2EV shots. Correction of chromatic aberration, purple fringing, and lens fall-off has also been applied at the raw development stage.

Control Point Placement

The placement of control points is at the seams between overlapping images. There is no need to have control points outside of these, the blending process just needs that the features match along the seam lines.

Nadir Shot

Taking a separate nadir shot to add to the panorama takes only a few extra moments, but can lead to more professional looking and immersive results. A nadir adapter simplifies matters but even without, it is straightforward to cant the camera directly over the spot where the tripod was located for the other shots and take an image of the ground. It is best to try to match the height of the camera to the other shots but in many cases, slight differences in height won’t be a problem for flat ground. If there is the possibility of parallax, then it is crucial to try to maintain entrance pupil position.

The nadir is connected to the azimuthal shots by 2 control points each. Using a narrowed tripod leg spread, the area of the nadir that needs to be patched can be minimised.

The nadir is connected to the azimuthal shots by 2 control points each. Using a narrowed tripod leg spread, the area of the nadir that needs to be patched can be minimised.

The nadir shot is masked out to eliminate the legs and define a small region to be inserted into the rest of the pano. Here, tripod leg shadows had to be excluded. Due to the position of the spot lights, it was difficult to place the tripod in a way that avoided them entirely.

In Hugin, the nadir shot is given its own lens so that the geometry can be optimised separately. , hence reducing the amount of geometric distortion that may be induced in the nadir shot to match the placement of the rest of the panorama.

Tripod Shadow Patch Shot

There was a particularly strong shadow of the tripod and camera that would need to be edited out in post-processing. Masks were used to exclude the shadows from the panorama.

A separate shot was taken with the camera and tripod moved about half a metre so that a clear shot of the ground without shadow could be taken. This shot is inserted to cover the shadowed area. Only a small section of the image is required, hence can be mapped quite effectively despite the large displacement of the entrance pupil. For longer shadows, a patching image may need to be imported multiple times and parts of it mapped into the panorama separately.

Final Output

Hugin can produce an exposure fused panorama which combined highlight and shadow detail in a natural looking way. The nadir and shadow patches will reduce the amount of postprocessing required. There are a few residual faint shadows due to other lights in the scene but these are very easily dealt with in Photoshop or other image processing programmes.

There are alternate methods of handling high contrast scenes, such as High Dynamic Range imaging and Tone-Mapping. Exposure fusion (e.g. using enfuse) is often simpler. Here, the inbuilt exposure fusion method was used, but more control over the final result can be achieved by exporting each exposure plane separately and using the command line options in enfuse.